|

Preschoolers at the Play House North are painting a colorful mural. This sensory activity helps children build social skills as they learn how to work together in a shared space and take turns using different materials. Young children learn with all of their senses. This art activity gives children the opportunity to actively use their sense of touch to explore the different textures of the materials. As they paint, they can see how each material paints differently. They are also experimenting with mixing colors and exploring how different textures create different patterns. Children are also developing motor skills as they use their hands to hold the brush and their whole arms to make the brush strokes. Best of all, they are also learning that they can create something beautiful together!

By Elia Rocha When I was little, my mom used to read to me from a book which contained Oscar Wilde’s fairy tales. The book was a Spanish translation of his complete works and it was only until years later that I realized that the stories there were first conceived in English; that El Príncipe Feliz was actually The Happy Prince, and that El Gigante Egoísta started out as The Selfish Giant. No matter. I love Oscar Wilde to this day, and even if I had never read anything else by him but those fairy tales he would still remain a hugely influential writer for me, because it is through him and his beautiful, lyrical, and haunting stories that I can trace my love of books and reading. In the story, The Happy Prince, a young royal who ignored the suffering of others during his lifetime, is reborn as a gilded and bejeweled statue and placed on a pedestal in the center of the city by the town councilors for all to admire. From his vantage point, he can see the pain and destitution of the city’s poor for the first time. Deeply moved, he asks the help of a passing swallow to peel the gold leaf from his body and pick the jewels from his eyes and sword and distribute them to help alleviate the suffering of his people. Touched by the prince’s plea, the swallow delays his flight south for the winter to help his new friend. When the statue is no longer beautiful, the town councilors tear the prince down. The swallow, having missed his chance to fly south for the winter, dies of cold. Later, God asks one of his angels to bring him the two most precious things in the city. The angel returns with the swallow, and the broken heart at the center of the statue. All these years later, I remember this story. I remember being moved by the friendship of the prince and the swallow and feeling angry that the town councilors would blindly ignore the love and sacrifice so evidently on display. But, it is more than the power of the story itself that makes it so memorable. Who knows how many times my mom read this to me. How many times I sat on her lap, or lay in bed next to her, while she recounted this allegory. How many times I stopped the story to ask a question or to ponder the reasons that the characters did what they did. This quiet, intimate ritual provides the ideal context and space to think these big thoughts.

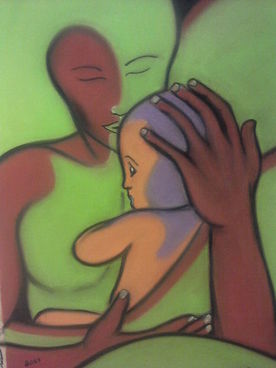

For many of us, books and stories are the first time we recognize that ideas can exist outside of our own direct experience. They are our first introduction to complicated moral, philosophical, and social questions. And, unlike movies or TV shows, they require the reader or listener to be an active participant and provide the pictures to go along with the words. When we are young, they also require a loving guide to lead us through the worlds these stories inhabit.  Papa et bebe by Bliu Pastels Papa et bebe by Bliu Pastels By Elia Rocha Most of the children who enroll in our Play House programs live with just one parent, and usually that parent is their mother. While fathers may be involved in their lives, more often than not that involvement is sporadic, unstable, and in many cases, marked by episodes of domestic violence. Certainly, the families we work with represent the extreme low end of economic, social, and household stability and are not necessarily representative of our larger society. They do, I think, however, show us where the major fault-lines lie which can so often threaten to split families apart. I won’t argue here that two-parent households are inherently better for children than one-parent households because so much depends on the capacity of mom or dad to provide a safe, nurturing, and consistent environment. Surely, a child is better off with one stable parent, than with two unstable parents. In these cases, one plus one definitely does not equal two. However, it is sometimes jarring to see the utter lack of any nurturing men involved in these children’s lives. Even within our own programs, having a male teacher is so rare as to seem an aberration. It is true that in the child development field, male caregivers are sadly few and far between. I think this has to do with an outdated but pervasive misconception that caring for young children is still woman’s work. Does this perception extend to father’s themselves? I hope not. I do think that whether or not we hold mothers more accountable for raising children than fathers, we are less surprised and more resigned when fathers are not around. That certainly does a disservice to all the fathers and other male caregivers who are providing for and nurturing children. I fear it also leaves many of the children we serve with the skewed sense that men - a whole segment of our population - are not there to care for them.  By Cheryl Ichikawa As teachers at Children Today, we understand the need to find the connection with our children. We know that each child that enters our classroom has a story, with trauma being part of that narrative. Forming an attachment with a primary caregiver is the critical first step to laying the foundation that will allow these children to build the courage and confidence to engage and explore their surroundings, as well as form relationships with their peers. As their teachers, we understand that the children that enter our classrooms come with a variety of needs that must be met before productive learning can begin. Some of these needs are basic. For example, we understand that if a child comes in hungry and tired, this will affect how they function and interact in the classroom. We are also aware that forming an attachment - building a trusting, unconditional and supportive relationship - will determine our effectiveness as caregivers and will translate into the social, emotional and cognitive progress of the children we serve. For some children, transitions are hard, whether from activity to activity or from caregiver to caregiver. For this reason, consistency, daily routines and verbal communication (talking through what is and will be happening) are important strategies that provide children with a predictable way of viewing their day and make them feel like they are in control of their daily experience. All of these things support the teacher-child relationship and a child’s ability to move through their day with confidence. As we watch the children progress in the toddler classroom, we constantly look for ways to connect. While some children need to be physically close to their primary caregiver to feel safe, other children can maintain their connection through eye contact or simple phrases, like “I see you” or “I’m right here.” We have a little girl that can be triggered seemingly without notice. One moment she can be cooperatively interacting with another child in an activity and the next she can be pushing, hitting or biting that same child. Some of these triggers can be so subtle, but we have learned them and now we can remove the child from the situation before something explosive happens. We can help her calm down and then quietly talk about the need to “be gentle” or “use her words.” Teachers will quietly sit with the child until she is ready to once again participate in the environment. What we have noticed in recent weeks is that her outbursts have lessened and her ability to safely interact with other children has significantly increased. When she feels overwhelmed or stressed, she has learned to remove herself from the situation by finding the teacher, often taking that teacher by the hand and leading her to a quiet space in the classroom, sitting on the teacher’s lap, sucking her thumb and laying her head on the teacher’s chest. This is her way of soothing herself. When she is ready, she will get up and continue her day. Attachment is about finding that connection. It’s about understanding and identifying each child’s changing moods and triggers. It’s about knowing what will happen when a child is tired or hungry or soiled or in need of some individualized attention. Each time a teacher is able to respond appropriately to the needs of a child, their relationship is strengthened and a deeper trust is established. It is from this foundation of trust that all things are possible.  By Dora Jacildo The greatest contribution we can make to the children and families we serve is to provide opportunities for the youngest children to develop healthy attachments to the caregivers and teachers in our programs. We know that many of the children enter our classrooms with great fear, anxiety, and anger. We know that being separated from their parent can be unbearable. We also know that it is our job to respond to children in a supportive, consistent, and nurturing manner in order to begin to satisfy the innate, genetically programmed need to bond with another person. Attachment, to us, means that we’re not only providing for their basic needs of food, rest, and safety, but that we are physically, socially and emotionally invested in every child. We understand that our staff’s ability to respond sensitively and appropriately to each child’s needs is what’s most important. We also understand that our ability to develop relationships with the children and their ability to bond with us sets the stage for how future social relationships may unfold. Every child enrolled in our program is assigned a primary caregiver. This person makes it their top priority to bond with the child by being physically close to her/him and by providing all of the basic care she/he requires throughout the day. It is our goal to have the child see their primary caregiver as the person they can cling to when they are upset and want comforting, and as the person they can count on to help them get their needs met. There have been countless times when I have walked outside into the playground and found children securely and affectionately being held by their primary caregiver. For some children, it’s the only way they can make it through the day. Attachment is a huge part of our curriculum. It is a foundational component that we address every day. We simply cannot expect children to grow and thrive if we neglect the most fundamental area of human development. Theorists have suggested that “there is a critical period for developing attachment (about 0-5 years). If an attachment has not developed during this period then the child will suffer from irreversible developmental consequences, such as reduced intelligence and increased aggression.” When we think about the consequences of the disruption of an attachment between a child and his caregiver, we logically make a commitment to ensure that for any child who is enrolled in our programs, there will be someone on our staff who will be crazy about him. |

AuthorVarious members of the Children Today staff contribute to these blog posts. Archives

July 2024

Categories |